Jewish Standard / Times of Israel

Why orange socks?

How a Chabad rabbi, whose public menorahs stand in Livingston and West Orange, finds meaning in art

By Deb Breslow December 11, 2025, 9:57 am

Although he has had no formal artistic training, Rabbi Yizchok Moully has found innovative and meaningful ways to transform nature, spirituality, and Judaism into Jewish pop art.

Rabbi Moully was born in Darwin, a coastal city in the Australian outback, a two-day drive from Melbourne or Sydney. “We were so far off the beaten path, there was no Jewish presence there,” he said.

So what was a good Jewish family doing in Darwin? “We weren’t ready to become a good Jewish family,” he said. “I was an only child born to hippies who lived on a commune with like-minded people.” He began life as a wild child, surrounded by nature and free-spirited family and friends.

Moully’s mother, Norah, was born in Alexandria, Egypt. Her family emigrated to Australia in 1956 during the Suez crisis. She grew up in Melbourne and eventually moved to Darwin, where Yizchok was born. But then, when he was 4 years old, “my grandfather got sick, we” — by then it was just Norah and Yizchok — “came down from Darwin to visit him,” Rabbi Moully said. She met Shimon Cowen, a Chabad rabbi, at her parents’ synagogue. “My grandfather wanted to connect us to our Jewish roots. Their conversation led to my being enrolled in Jewish day school at Yeshiva College in Melbourne.”

On the day Rabbi Moully started school, his grandfather died. But Rabbi Cowen remained an advisor to his mother, “who was very spiritual and was developing a newfound love of Judaism,” her son said; he recalls Rabbi Cowen as instrumental in helping his mother plan their future. “We were directed to move to Israel to live on a religious kibbutz — to surround ourselves, as we had in Darwin, with nature and like-minded people.”

Paperwork was gathered, money was saved, and the small family got on a plane. Instead of going through Asia to get to Israel, their flights stopped first in Los Angeles and then in New York, where they were connected with a family who hosted them in Crown Heights. They planned to stay there for a short time before continuing to Israel.

“It was Rosh Hashanah 1985, and while we were there, people suggested we write a letter to the Lubavitch rebbe for a blessing, for ‘soul wisdom,’ in preparation for our continued journey to the kibbutz in Israel,” Rabbi Moully said. “My mother wrote her letter and the response we got was ‘Stay here for the time being and accomplish what you’ll accomplish through friends.’

“My mother believed in following the advice of the rebbe, assuming it meant she could find a husband, so we stayed, and we stayed, and we stayed — for four and a half years.”

Yizkok was 6 years old when he and his mother landed in Crown Heights. His mother found a job in Brooklyn, and he went to school in Crown Heights, at Chabad-Lubavitch world headquarters at 770 Eastern Parkway. He was there through fourth grade and learned Yiddish and some Hebrew,

“The energy was palpable in this area,” he said. “It was like Simchat Torah on steroids.”

A paint-spattered Rabbi Yizchok Moully stands in front of one of his Chanukah murals.

Every Shabbos morning, he got a blessing from the rebbe. “Marinating in the energy of the chasidim in Crown Heights meant something to me,” he said.

“When my mother’s pension ran out, she wrote again to the rebbe and he advised us to move back to Melbourne, where I continued my studies at Yeshiva College,” he continued. “We never made it to Israel, we never made it to the kibbutz.” But back in Australia, “while it was a drastic change from Crown Heights, I fit back into the yeshiva system.”

After high school, Rabbi Moully enrolled in the Rabbinical College of Australia and New Zealand and studied there for two years. Then, in 1998, he returned to the United States to continue his studies for two years at the Rabbinical College of America-Lubavich in Morristown. Then it was back to Australia, where he became a mentor, a shaliach, to the younger boys in Melbourne.

His mother met her husband, Moshe Elkman, when Moully was 15, and they married, so her future seemed secure. But Rabbi Moully continued to wonder about his own path. “What did the rebbe want of me?” he asked himself. “What did he have in mind for me?”

He believed it was to share his love of Judaism, so he continued to learn and teach. He got smicha — rabbinic ordination — at the Rabbinical Academy of Venice, Italy. In 2002, he met his future wife, Batsheva Brown, in Toronto.

“We got married, I did one year of kollel in Melbourne, and since my wife and I were aligned in our desire to go on a shlichut to North America, in 2004 we moved to the United States,” he said. Rabbi Mendy and Malkie Herson of the Chabad Center of Greater Somerset County in Basking Ridge hired him, the couple moved to Hillside, and he was the youth rabbi there from 2004 to 2014, supporting educational and holiday programs, Hebrew school, bar and bat mitzvah training, and services.

But “while I loved serving the community under Rabbi Mendy, I needed a creative outlet,” Rabbi Moully said. So he bought a Canon EOS Rebel digital camera and began taking photos of nature — rivers, streams, and forests around Morristown. He took family portraits and videos for Chabad events. “But I wanted more,” he said. “When I came across the silk- screening process, I found my passion.

“Without knowing how to paint, I could still make a painting.”

He made his first piece of silkscreen art on an 8×8 canvas of a chasid on a public pay phone — which at the time was a contrast between the contemporary and the timeless, but by now contrasts the antiquated and the timeless.

Rabbi Moully said that it took him almost a year to master the technique of silk screening, which “as a process is a continuation of photography,” he said. “There were always Judaic elements in my work. I was inspired by Andy Warhol and Jewish pop art.” Rabbi Moully visited many galleries; in Lambertville, he met the owner of one called Art Is Zen. “He was willing to show my work,” Rabbi Moully said. He recalls feeling a harmony between his responsibilities as a rabbi and his desire to create art.

This menorah stands by the South Street Seaport and the Brooklyn Bridge as dusk falls.

“It was all balanced until it wasn’t,” Rabbi Moully said.

“My emotional energy and passion was moving toward the arts versus my rabbinical responsibilities. We’d been in Basking Ridge for 10 years and I turned to my rabbi and mentor, Rabbi Yossi Serebryanski, the Chabad rabbi at the University of Denver for guidance. He shared with me something that shifted my perspective forever: ‘The question isn’t should you paint or not? The question is how do you take the gifts that God gave you to impact the world in a meaningful way?’

“He knew I couldn’t do both. Art was my gift. I couldn’t outsource my art, my expression. My creativity was a reflection on Yiddishkeit, on Judaism, on chasidic rituals. Bringing these two worlds together was a testament to my uniqueness.”

He couldn’t devote himself to both shlichut and art, so Rabbi Moully chose art. Now, “I am blessed to do art full time,” he said.

Rabbi Moully is 47. He and Batsheva have six children, who range in age from 22 to 9. His family’s home and his studio, Moully Arts, are in Hillside.

Rabbi Moully works in a range of forms, from pop art to abstract painting to murals and interactive pieces. “There are three basic elements to creative expression,” he said. “What you say, how you say it, and how you share it with the world.”

In 2018, in response to the Tree of Life shooting in Pittsburgh, where 11 people were murdered at Shabbat services and six others were wounded, the Moully Art Team — his assistant and his family — drove an RV around New York and New Jersey. Rabbi Moully painted a menorah on a canvas that he called “Light Over Darkness” and hung it on the side of the RV. “We brought a bundle of colorful iridescent markers wherever we went and invited people to use them to write their mitzvot on the dark background of the painting,” he said.

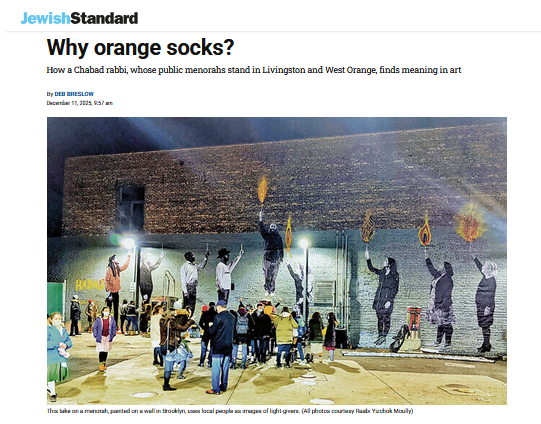

Since the foundational element of a menorah is creating light from darkness, in 2020 Rabbi Moully partnered with Chabad of Clinton Hill and students from Pratt Institute of Art to show nine members of a Brooklyn community each sharing their unique light. “I took a photo of four women holding up candles, Statue of Liberty-style, and four men facing them, also holding up candles,” he said. “The rabbi was the menorah’s shamas.” In the lead up to Chanukah, he took the photos, then a week later he hung the 20-foot-tall mural on a wall on Myrtle Avenue in Brooklyn.

Every night of Chanukah he invited a local artist to paint one of the flames on the menorah throughout the holiday. “I also created the Living Lights Art installation in 2021,” he said. “It was an 18-foot-wide, 10-foot-high touch-sensitive menorah that could light up for each night of Chanukah. Families and communities participated as we traveled to museums and malls in New York and New Jersey. When someone touched an arm of the menorah, it lit up.”

Rabbi Moully’s work has evolved from canvas to steel. Starting in 2017, he has been commissioned to create permanent three-dimensional large-scale menorah sculptures. One, commissioned by the South Street Seaport in lower Manhattan overlooking the East River, is on display every Chanukah.

Children write these wishes for peace on “Light Over Darkness.”

“Much of my work is bright and colorful, but some of my work is inspired in response to tragedy,” he said.

He has designed permanent sculptures and murals in response to terrorist attacks. His Tradition With a Twist menorah will be going up in the square where there was a terrorist attack in Boulder, Colorado — that happened earlier this year, when a murderer threw Molotov cocktails at a group gathering in a walk to support the hostages Hamas was holding in Gaza.

He also designed a mural commemorating the victims of the terrorist who killed three people in 2019 in a kosher grocery store in Jersey City, as well as a police officer killed in preparation for that attack. “The mural hangs permanently on a building wall on 12th Street in Jersey City,” he said. “It can be seen by thousands daily as they enter the Holland Tunnel.”

Rabbi Moully has ideas and concepts for a memorial to the victims of October 7; he’s calling it “Am Yisroel Chai.” He is also developing a monument honoring the October 8th Jews, “the Jewish people who are living in the wake of October 7.”

One of his works, designed in 2009, was created on a small piece of canvas, 10 inches tall and 30 inches wide. On its yellow background, in silhouette, 12 chasidic men walk in the same direction. “One of the 12 gentlemen is wearing orange socks, and that’s me,” Rabbi Moully said. It’s a bit of self-portraiture; “Orange Socks is about conforming and being an individual at the same time. It’s fun, it’s offbeat, it’s become my trademark.” He wears orange socks — even to his own wedding. Over the years, Orange Socks has created a sort of cult following. People resonate with the idea of finding your creative expression in a larger community.

Dr. Noa Lea Cohen, an art lecturer, curator, and journalist of contemporary Jewish art in Israel, asked Rabbi Moully if she could use the orange socks image to help her Bar-Ilan University art students see the lighter side of art. As part of the 2017 Jerusalem Biennale, she created a full pavilion with a show called “Pop-thedox – Ultra Orthodox Pop Art.” Rabbi Moully’s contribution to the group show was the Orange Socks piece, redone to life size, hoping to invite people into the creative process.

Rabbi Moully believes we each have a unique story to tell. In May 2024, he started hosting a weekly podcast, an exploration of Jewish artists and art that he calls Orange Socks.

Two of Rabbi Moully’s public menorahs are on display locally. One is at the Friendship Circle in Livingston, and the other is at Chabad of West Orange. There are others in Florida, Maryland, New York, Colorado, California, Toronto, and Montreal. “For me, every day is erev Chanukah,” he said.

“My art reveals an explosion of energy where I see God through a new lens, where I connect with my people through mitzvot, memories, blessings, rituals and traditions,” Rabbi Moully summed up. He believes that his creativity is rooted in his childhood in Australia — climbing trees, climbing roofs, getting into mischief. “I encourage the younger generation to try and fail, to seek and find their own voices, to journey toward their own expression,” he said.

Learn more about Rabbi Yitzkok Moully and his art at moulllyart.com.